Research Objectives

Understand the growing issues of anxiety and substance addiction among today’s youth. Examines the impact of these problems on young lives, it underscores the urgency of addressing them. Reviews current prevention and intervention methods to provide a clear understanding of how to support youth struggling with these issues.

Keywords

Mental Health, Adolescents, Anxiety, Depression, Addiction.

Bio

Rituu Guptaa, born and raised in the scenic valleys of Dehradun, India, is a passionate advocate for justice and empowerment. With a career spanning over 25 years as a clinical psychologist and counsellor, she has been a guiding light for many in overcoming life’s challenges. Rituu firmly believes in the inherent resilience and strength within each individual, empowering her clients to navigate through adversity with courage and determination. She epitomizes the adage “Be the change you want to see,” inspiring others to tap into their inner resources and embark on a journey of self-discovery and transformation.

Bio

Uddayvir Singh is a dedicated student with a clear ambition to pursue a career in medicine. Currently, he is rigorously studying a diverse range of subjects including Chemistry, Biology, Physics, Psychology, and Mathematics, laying a robust foundation for his future medical studies. His academic journey began with a strong performance in his I/GCSEs, where he developed a keen interest in the sciences and an understanding of the intricate workings of the human body. With a passion for learning and a commitment to excellence, Uddayvir is keen to make significant contributions to the field of medicine in the future.

Abstract

The prevalence of mental and psychological disorders among younger generations has significantly increased in recent years, raising critical public health concerns. This literature review examines the factors contributing to this rise and explores various disorders affecting today’s youth. Using a systematic search and analysis of scholarly articles from databases such as PubMed, PsycINFO, and Google Scholar, the review identifies key studies on the prevalence, correlation, and determinants of depression, anxiety, substance addiction, among adolescents and young adults, with a specific focus on anxiety and substance addiction.

A critical appraisal framework evaluates the methodological rigor and quality of included studies, ensuring reliable and valid findings. By synthesising current research, the review elucidates the complex interplay of genetic, environmental, social, and cultural factors influencing the mental health landscape of younger generations.

This understanding is essential for developing targeted interventions and promoting resilience among youth facing mental health challenges. The review also highlights the impact of technology, social media, academic pressures, family dynamics, and socio-economic disparities on mental health outcomes. By critically evaluating existing literature, the review offers insights into potential research avenues and underscores the need for comprehensive, evidence-based approaches to address the growing crisis of mental health disorders among younger populations.

Introduction

Many studies have reported an increase of anxiety related symptoms within the past decade, but the exact prevalence remains unknown. Anxiety disorders are complex and often under-diagnosed because they can manifest a variety of physical and psychological symptoms (Back, Waldrop, & Brady, 2070). Anxiety is commonly identified as a sense of dread or apprehension, which is often accompanied by physical complaints such as headache, stomach-ache, muscle tension, shortness of breath, shakiness, and dizziness. Sudden and intense anxiety for no apparent reason is referred to as a panic attack (Marks, 7987). Though not life threatening, anxiety disorders often impair functioning and quality of life. It is a main contributor to mental health diagnoses and can often be an offshoot or precursor to additional psychiatric disorders such as depression or further anxiety conditions. The social and academic pressures on today’s youth, in addition to an uncertain economic and political climate also contributing to loss of identity, have been presumed as an attributing factor to anxiety prevalence (Baumeister & Muraven, 7996) (Baumeister & Muraven, 7996). These factors are expected to increase competition in the job market and thus increase the requirements for higher education and standard of living. This, in turn, brings higher expectations upon our youth and a scarce job market for unskilled workers The recent shift towards a global community has proposed increased opportunities for travel and a wider and more competitive job market on a world scale. This has created a mindset of necessity for today’s youth to achieve and be successful on an international platform. Failure to meet those more rigid standards could contribute to a sense of inadequacy and additional pressures high in causative factors for anxiety conditions.

With the steady dominance of mental and psychological disorders among today’s youth, researchers aim to decipher the primary catalysts and aid pathways to potential solutions. A media storm of technological advancements, social networking, and added pressures such as academic targets and financial uncertainties have all played a supportive role in the accelerated prevalence of mental disorders within the millennial and post- millennial generations. Anxiety and substance addiction are the primary focus due to noting the substantial rise of diagnoses within these specific areas and the dire negative implications they pose to a person’s mental health and future outcomes. This research study will seek to comprehensively understand the surge of mental and psychological disorders among today’s youth, specifically anxiety and substance addiction. By synthesising quantitative and qualitative data over a multi-disciplinary arena, we hope to identify the causative factors that have contributed to the escalation of these conditions, attempt to quantify the severity of these issues, and explore potential preventative and intervention measures.

Aim

This literature review aims to understand and discuss the following:

-Growing issues of anxiety and substance addiction among today’s youth.

-Examines the impact of these problems on young lives, it underscores the urgency of addressing them.

-Reviews current prevention and intervention methods to provide a clear understanding of how to support youth struggling with these issues.

Methodology

This review examined literature on the rise and causation of mental and psychological disorders among today’s youth, focusing on anxiety and substance addiction. Despite the increasing number of studies on the prevalence of these disorders, understanding why this increase is occurring remains crucial. By identifying the causes, prevention strategies can be developed to avoid a lifetime of coping. The review included literature from journals and various youth samples, ranging from clinical populations to college students. Although the severity of anxiety and some substance disorders varied, the issue is relevant to all youth, especially those facing the stresses of higher education. The review explored the various causes and issues surrounding diagnosable anxiety disorders, noting similarities to substance addiction issues.

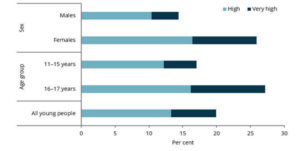

In the National Health Interview Survey, 6.8% of Americans (about 77 million people) had at least one depressive episode in the year prior to being surveyed. Of these, 80% reported some level of functional impairment in doing work, school, or housework, or in their interpersonal relationships. In the United States, the leading cause of dropout in high schools is depression related (Rones & Hoagwood, 2007). Figures for other anxiety disorders are not easy to split from figures for behaviour disorders, but one UK study found that 3.3% of children aged 4-76 had an anxiety disorder (Ford, Goodman, & Meltzer, 2003). In an Australian survey, it was found that 74.4% of 4-77-year-olds, and 27% of 78-24-year-olds were assessed as having either a “high” or “very high” level of psychological distress (based on K-70 scores) (AIHW, 2027). In twelve months prior to the survey, 7.7% or around 300,000 young Australians had experienced an anxiety disorder, while the rate of affective disorders for the same period was 5.7%. With the growing realisation of the seriousness of anxiety disorders and their grave outcomes on life impairment, it is important that they are not ignored in research and people continue to try to understand them. Figure 7 illustrates Psychological Distress Levels Among 11-17 Year Olds, Categorised by Age Group and Gender, 2013-2014. An understanding of this is needed to persuade funding bodies to support further research into anxiety disorders. High prevalence rates and serious outcomes in younger people may potentially affect the future productivity of youths and have implications for future generations.

3.1 The Interplay Between Anxiety and Substance Addiction

The enhanced predisposition of those with anxiety toward consuming addictive substances is well documented. Anxiety was positively associated with a wide range of lifetime substance use:

ten of the eleven substances studied (cannabis, inhalants, cocaine, hallucinogens, heroin, ecstasy, prescription medications, alcohol, and nicotine) showed positive associations with anxiety (Conrod, Castellanos-Ryan, & Mackie, 2077) Though among specific anxiety disorders, only social anxiety has been consistently associated with substance use and abuse, the data is more robust for alcohol abuse, especially among male subjects. A possible explanation is that those with social anxiety utilise alcohol to ameliorate the negative emotions associated with the disorder (Vasey, 7995).

There are functional ramifications of the relationship between anxiety disorders and substance abuse. Following exposure to anxiogenic stress, individuals with anxiety disorders have been shown to be more vulnerable to developing an addiction to an abused substance. The seeking of intoxication and subsequent chronic abuse of a substance can be seen as a method of self-medication to reduce the negative affect and emotional suffering associated with the anxiety disorder (Cisler, Olatunji, Feldner, & Forsyth, 2009).

Figure 1. (AIHW, 2021)

The acute intake of an abused substance has an immediate effect on the brain and neurotransmissions, potentially causing a rapid psychological shift from negative affect to relief. This shift can serve as positive reinforcement for continued substance use and in the gradual formation of an addiction. High comorbidity rates are seen in the more severe anxiety disorders, with ten of the eleven substances studied (cannabis, inhalants, cocaine, hallucinogens, heroin, ecstasy, prescription medications, alcohol, and nicotine) showed positive associations with anxiety (Conrod, Castellanos-Ryan, & Mackie, 2011) Though among specific anxiety disorders, only social anxiety has been consistently associated with substance use and abuse, the data is more robust for alcohol abuse, especially among male subjects. A possible explanation is that those with social anxiety utilise alcohol to ameliorate the negative emotions associated with the disorder (Vasey, 1995).

There are functional ramifications of the relationship between anxiety disorders and substance abuse. Following exposure to anxiogenic stress, individuals with anxiety disorders have been shown to be more vulnerable to developing an addiction to an abused substance. The seeking of intoxication and subsequent chronic abuse of a substance can be seen as a method of self-medication to reduce the negative affect and emotional suffering associated with the anxiety disorder (Cisler, Olatunji, Feldner, & Forsyth, 2009). The acute intake of an abused substance has an immediate effect on the brain and neurotransmissions, potentially causing a rapid psychological shift from negative affect to relief. This shift can serve as positive reinforcement for continued substance use and in the gradual formation of an addiction. High comorbidity rates are seen in the more severe anxiety disorders, with addicts making up as much as 20% of those with social anxiety disorder and panic disorder. This represents a near doubling in the odds of being addicted to alcohol and a 4- 5-fold increase in the odds of addiction to another drug. Time constraints and participants means having the presented literature has been focused on adults, and it is important to consider further the link between anxiety disorders and substance abuse in adolescents. Numerous studies have found strong associations between psychiatric conditions, both treated and untreated, and subsequent academic achievement (Rones & Hoagwood, 2001).

A British birth cohort study found that parental report of ’emotional disturbance’ at age 16 was associated with reduced occupational attainment at age 26. Those who met criteria for depression at ages 15 and 16 in another study were found to have lower grade point averages, educational attainment, and occupational functioning ten years later, as compared with their non-depressed counterparts. Although it is difficult to dissociate the effects of comorbidity, substance abuse, medication, and the underlying disorder itself, the clear impact on educational functioning is compelling (Fergusson & Lynskey, 1998).

3.2 Treatment Approaches and Modalities

Treatment types in general practice the recommended approach for choosing the right treatment for each specific problem should involve considering recent advancements. While primary care is typically sufficient for managing mental health issues in young individuals, it may not always be the ideal option. Psychological therapies can be administered in primary care, but specialists may be required to provide more specialised assistance or guidance. When selecting the most suitable form of treatment, factors such as the problem’s severity, persistence, associated functional impairment, and the specific preferences of the child or young individual and their family should be taken into account. It is crucial to recognise that early intervention at the least severe level is often the most effective approach in addressing most mental health problems.

3.3 Cognitive- Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

The focus in CBT is to redefine irrational beliefs that may lead to emotionally distressing events, by a series of teaching a client to monitor and identify their thoughts and attitudes. With CBT, the patient is thought to be equipped to alter those thoughts and this, in turn, will change their reaction to those events (Jones & Pulos, 1993). Once the patient has mastered the reconstruction of events to outcomes that can relieve emotional distress, a clear plan of gradual exposure to the distressing events can now be tackled with a defined cognitive and behavioural formula that will not cause distress (David & Szentagotai, 2006). This is a process that can be seen in the treatment of anxiety disorders where people will often avoid certain situations and events and thereby deny themselves the opportunity to alter an outcome to less distressing or treat a fear which in reality is not threatening. The end of treatment with CBT is always termination with a conscious use of the coping methods learned by the patient and with a reinforcement of the new methods as a way of life. Szasz, 1960 and Scheff, 1966, and many other sociologists of the labelling theory within mental illness, have had a pivotal view in the criticism of psychological treatments (Krohn, Lizotte, & Hall, 2009). They have researchable evidence that shows the process of how a patient of a mental illness being subjected to a certain therapy or medical treatment is, in fact, conforming to the label of their illness and in many cases getting worse or prolonging the illness. This is due to the social construction of the label; the patient is stigmatised to being who has a mental illness and the only way they can escape the label is to consider themselves as cured and that the treatment failed to remove the irrational belief that led to the distressing events. This view of CBT can be seen as somewhat positive, in the case that there is the variability for individual or group therapy and that the treatment is a focused attempt at changing specific symptoms. The different techniques and methods used in CBT show that it is a viable treatment option for many common mental disorders and its direct and problem-based approach make it favourable in the medical community in today’s age.

3.4 Medication Management

In particular, anxiety medications play a role in the self-medication of anxiety conditions. A recent study with over 1000 college students showed that 9 out of 10 of these individuals sought out various medications, both legal and illegal, to get them through their anxiety problems. Hence, the opportunity for a student to abuse anxiety medications is very high. Tolerance can develop for anxiety medications, causing an individual to need more and more of this drug to calm down.There are various types of medications used to treat anxiety. Acute treatment for anxiety is usually a prescription for a type of benzodiazepine. Benzodiazepines are a class of compounds that are widely used for the treatment of anxiety and insomnia. These types of medications are known to be effective and fast-acting for relief of anxiety symptoms; however, the long-term use of these medications is not recommended and can be habit-forming. Long-term maintenance medications include certain SSRIs and buspirone, which are safer compared to benzodiazepines and do not induce a dependency. Beta- blockers are also used on an as-needed basis for control of performance anxiety. Any of these medications should be utilised while combined with psychotherapy for the best effectiveness and long- term results.

3.5 Holistic and Alternative Therapies

Holistic treatment looks at the situation as a whole and tries to decide what elements of life are causing the individual distress. Alternative treatments may include activities such as yoga, Tai Chi, or meditation. It is possible that alternative treatment may be mixed with herbal medicine, for example taking herbal supplements to relieve anxiety symptoms. Yoga and meditation have been scientifically proven to decrease anxiety and stress levels. Tai Chi has the same effect, although it is not as well researched; recent studies have proven that herbal supplements are just as effective as prescription medication, and patients view them more positively. Many patients never return to herbal medicine once they have been prescribed psychiatric drugs, and it is likely that there are differences in people seeking herbal treatments and prescription drugs. Mixing the two treatments is ill-advised and it can be dangerous, patients should seek advice from an herbal practitioner or homeopathic doctor, who is likely to be critical about mixing alternative and prescription remedies. Engaging in physical exercise increases the serotonin in the brain, which leads to improved mood and decreased anxiety. This may be anything from going for a run, to taking a dog for a walk in the park. There are a vast number of activities which people can undertake to increase their fitness, and it is up to the individual to find something that they will enjoy and will maintain. The exercise recommended to combat anxiety would be that which gets the heart pumping, as this is what is required to increase serotonin. Nutrition is also important, and maintaining a healthy diet will improve an individual’s general health and resistance to illness. Step one is avoiding junk food, which is high in sugar and fat. High levels of sugar cause hyperactivity and elation due to increased blood sugar, however this is followed by fatigue and depression when it drops. A good diet does not simply mean not eating bad food, and it is important that people eat sufficient amounts of good, nutritious food. It may involve some research and many people are unaware of the nutrients that they are supposed to be taking. It may be necessary to see a professional nutritionist who can advise on meal plans and diets; this is a long-term investment which will lead to improved mood, self-esteem, and confidence. The overall effect of alternative therapies is a positive one, and successfully removing an anxiety sufferer from their problem. At this stage a person would no longer be classified as mentally ill and would have achieved a high level of mental health. This is different to the aim of removing a person from severe depression to a state of nothingness, and it is difficult to weigh up the cost efficiency of the two as the effect of removing depression is an increased suicide risk.

3.6 Support Groups and Peer Counselling

An effective intervention for youth mental health is support groups that focus on social skill building and self-esteem activities. These groups help normalise experiences, as shown in an anxiety study where clients felt relief discovering others shared similar issues (Durlak & Wells, 1997).

The social context of groups can harness peer pressure positively. According to Bandura’s social learning theory, youth learn coping behaviours by modelling others (Koutroubas & Galanakis, 2022). Support groups provide a setting that teaches healthy coping habits, especially beneficial for socially anxious youth. They offer exposure therapy and help generalise coping skills through homework tasks. While group CBT can treat adolescent depression, research favours individual therapy for severe cases, self- harm, and complex depression, as recommended by NICE guidelines (NICE, 2022). Despite their accessibility and cost-effectiveness, research on support groups for youth anxiety and depression is limited, even though they are effective for adults (Gibbons, et al., 2010). Prioritising the development and research of group-based interventions is essential for improving youth mental health.

3.7 Future Directions and Research Implications

Results have highlighted an increase in youth mental health problems and drug use as a temporary escape. Explanations focused on adolescent experiences, and while predictions were not tested within problem behaviour theory, future research could validate these hypotheses. Reassessing future generations’ mental health will be crucial. Today’s youth benefit from technological advancements, with new media and computers standard in developed countries. Technology has educational benefits, but its impact on mental health is mixed, potentially leading to issues like internet addiction. Conversely, technology can aid in prevention through educational resources.

Longitudinal studies following current youth to evaluate these theories would be valuable. The overlap between mental health and drug abuse, such as self-medication in depressed adolescents using prescribed antidepressants, suggests these fields may merge. It’s not a question of whether youth face problems but what will come next. Anxiety disorders often lead to other issues, including depression.

Understanding these sequences in adolescence requires ongoing research and integration with existing explanations.

3.8 Identifying Protective Factors and Resilience

Other than targeting the risk factors, identifying, and building on the protective factors and resilience of the youth is also an important means of preventing youth mental disorders. Protective factors are influences that reduce the impact of early stressful life events and act as a shield against the progression from stress to mental disorder. It was found in a cross-sectional study in Victoria, Australia that the common protective factors amongst young people with high levels of mental wellbeing were the possession of good life skills (including social, personal, and study skills, and skills related to future employability) and participation in structured and prosocial (including voluntary) activities. These factors were associated with mental wellbeing in youth across the range of socio-emotional problems and levels of functioning. On the other hand, poor mental wellbeing was strongly linked with the young person not being in education and employment. Although the presence of good life skills and the engagement in structured and prosocial activities are considered protective, a recent study found that the intrinsic belief in the value of the future of these young people was the most important factor in determining whether the skills and activities act protectively. This profound finding presents a potential intervention point for enhancing mental wellbeing amongst Australian youth.

Risky behaviors and poor physical health are common in young people with mental disorders and have been described as markers of an underlying continuum of social and emotional problems (Salkovskis, 1991). There is a bidirectional relationship between poor physical health and mental disorders, and it is likely that a strong focus on improving the physical health of individuals with mental disorders will reap its own benefits in terms of improved mental wellbeing. Development of interventions targeting health behaviours and early medical treatment of youth mental disorders may be a further investment in the mental health continuum of future generations (Côté, 2009). . A recent study has shown that for those individuals at the severe end of the continuum, premature death or decreased life expectancy is likely and represents a major public health issue. Suicide is the leading cause of death in people aged 24 years or younger in Australia and New Zealand, and for these reasons, it is important to enhance the continuum of care for young people with mental disorders until their general health and life expectancy more closely resembles that of people without mental disorders. This might also be considered for at-risk populations of youth showing socio-emotional problems before the point of diagnostic mental disorder in order to reduce the prevalence and burden of these problems.

One of the most potentially modifiable factors of mental disorders in youth is a family history of mental and substance use disorders. It is well known that there is both a strong genetic and environmental risk from parental mental illness, and a recent study has estimated that 15-20% of children are at risk of developing a mental disorder due to a parental history. This has been linked to poor parent mental health and disturbances in parenting practices, which can result in the exposure of these children to a range of socio-emotional problems. The negative effects of parental disorders are particularly concerning given the potential to prevent disorders in both the parents and children and in terms of the high human and economic burden from disorders across the lifespan. As such, there is great potential to prevent the development of mental disorders in these children through the improvement of parent mental health and parenting practices, and this may also serve to protect against disorders developing in subsequent generations.

3.9 Addressing Cultural and Socioeconomic Disparities

There are particularly important issues to consider in the context of anxiety and substance addictions in the young, and that is of culture and socioeconomic status. Studies have shown that members of ethnic and racial minority groups in the United States are less likely to receive diagnosis and treatment for their mental illness, have fewer positive attitudes toward mental health, and are more likely to use emergency mental health care or general medical services rather than mental health specialists (Stephens, Bohanna, & Graham, 2017).

Research also indicates that even when minorities are diagnosed with mood, anxiety, or substance abuse disorders, they are still less likely than the white majority population to receive any treatment (McHugh, Hearon, & Otto, 2010). It is believed that the disparities occur because ethnic and racial minorities have less access to mental health services, are less likely to seek help, and are more likely to receive poor quality care. This is especially problematic as rates of anxiety, depression, and substance misuse are often the same or sometimes higher for minority groups than the white majority population. This section aims to discuss some potential reasons for these disparities and how they can be addressed to provide better quality care for those affected by anxiety and substance addictions.

The surge of mental and psychological disorders among today’s youth has become a growing area of interest for researchers, clinicians, educators, and parents. Given that mental disorders usually have their onset in childhood and adolescence, it is of vital importance to understand why this disturbing trend is occurring, what are the consequences in terms of youths’ well-being, and what can be done to prevent it. In this paper, we have reviewed the evidence of the past 50 years and have seen a dramatic increase in rates of a variety of mental disorders among children and adolescents. This has been shown for different types of disorders, in different countries, and by many measures of mental disorder. The review covered the prevalence of youth mental disorders and their impact; the changing rates of disorders; the significant link between mental disorders and mental health services use; and clinical severity/detection of disorders.

The evidence points to a complex and as yet not fully understood mix of contributing factors to the increase in youth mental disorders that is almost certainly multi-determined. Pressing areas for further research exist. This includes the reasons for the wide variation in rates of disorder across developed countries, and why youth today appear to be so much more distressed than those of the past. For the sake of today’s youth and of future generations, it is hoped that research that seeks to understand the origins of this trend will continue to be prioritised. . In particular, a greater focus on prevention rather than cure is needed. Given the clear evidence of the potential for adverse impacts of mental disorders of youth well into adult life, every effort should be made to reduce the prevalence of these disorders among young people today.

The increase in mental and psychological disorders is now alarmingly high and this research study has shown they are often more prevalent than other health issues. This is now the time for psychological health to stand on its pedestal and receive the recognition it deserves. High rates of anxiety and substance addiction in youth may serve as a wake-up call-in mental health recognition. It can be hoped that mental health will now start to receive more funding and research tipping towards the provided better care and options for adolescents in the future.

References

AIHW. (2021, 06 25). Mental illness. Retrieved from Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/mental- illness

Back, S. E., Waldrop, A. E., & Brady, K. T. (2010). Anxiety in the context of substance abuse. In D. J. Stein, E. Hollander, & B. O. Rothbaum, Textbook of anxiety disorders (pp. 665–679).

American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. Baumeister, R. F., & Muraven, M.(1996). Identity as adaptation to social, cultural, and historical context. Journal of Adolescence, 405– 416.

Cisler, J. M., Olatunji, B., Feldner, M., & Forsyth, J. P. (2009). Emotion Regulation and the Anxiety Disorders: An Integrative Review. Journal of psychopathology and behavioural assessment, 68–82.

Conrod, P. J., Castellanos- Ryan, N., & Mackie, C. (2011). Long-term effects of a personality-targeted intervention to reduce alcohol use in adolescents. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 296–306.

Côté, E. J. (2009). 9 Identity Formation and Self- Development in Adolescence. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. .

David, D., & Szentagotai, A. (2006). Cognitions in cognitive-behavioral psychotherapies; toward an Integrative Model. Clinical Psychology Review, 284–298.

Durlak, J. A., & Wells, A. M. (1997). Primary Prevention Mental Health Programs: The Future is Exciting. American journal of community psychology, 233–243.

Fergusson, D. M., & Lynskey, M. T.(1998). Conduct Problems in Childhood and Psychosocial Outcomes in Young Adulthood: A Prospective Study. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 2-18.

Ford, T., Goodman, R., & Meltzer, H. (2003). The British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Survey 1999: the Prevalence of DSM-IV Disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 1203–1211.

Gibbons, C. .., Fournier, J. C., Stirman, S. W., DeRubeis, R. J., Crits-Christoph, P., & Beck, A. (2010). The clinical effectiveness of cognitive therapy for depression in an outpatient clinic. Journal of affective disorders, 1-3.

Jones, E. E., & Pulos, S. M. (1993). Comparing the process in psychodynamic and cognitive-behavioral therapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 306–316.

Koutroubas, V., & Galanakis, M. (2022). Bandura’s AIHW. (2021, 06 25).

Mental illness. Retrieved from Australian Institute of Health and Welfare: https://www.aihw.gov.au/rep orts/children-youth/mental- illness.

Back, S. E., Waldrop, A. E., & Brady, K. T. (2010). Anxiety in the context of substance abuse. In D. J. Stein, E. Hollander, & B. O. Rothbaum, Textbook of anxiety disorders (pp. 665–679).

American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. Baumeister, R. F., & Muraven, M. (1996). Identity as adaptation to social, cultural, and historical context. Journal of Adolescence, 405– 416.

Cisler, J. M., Olatunji, B., Feldner, M., & Forsyth, J. P. (2009). Emotion Regulation and the Anxiety Disorders: An Integrative Review. Journal of psychopathology and behavioural assessment, 68–82.

Conrod, P. J., Castellanos- Ryan, N., & Mackie, C. (2011). Long-term effects of a personality-targeted intervention to reduce alcohol use in adolescents. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 296–306.

Côté, E. J. (2009). 9 Identity Formation and Self- Development in Adolescence. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. .

David, D., & Szentagotai, A. (2006). Cognitions in cognitive-behavioral psychotherapies; toward an Integrative Model. Clinical Psychology Review, 284–298. Durlak, J. A., & Wells, A. M. (1997). Primary Prevention Mental Health Programs: The Future is Exciting. American journal of community psychology, 233– 243.

Fergusson, D. M., & Lynskey, M. T. (1998). Conduct Problems in Childhood and Psychosocial Outcomes in Young Adulthood: A Prospective Study. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, 2-18.

Ford, T., Goodman, R., & Meltzer, H. (2003). The British Child and Adolescent Mental Health Survey 1999: the Prevalence of DSM-IV Disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 1203–1211.

Gibbons, C. .., Fournier, J. C., Stirman, S. W., DeRubeis, R. J., Crits-Christoph, P., & Beck, A. (2010). The clinical effectiveness of cognitive therapy for depression in an outpatient clinic. Journal of affective disorders, 1-3.

Jones, E. E., & Pulos, S. M. (1993). Comparing the process in psychodynamic and cognitive-behavioral therapies. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 306–316.

Koutroubas, V., & Galanakis, M. (2022). Bandura’s Social Learning Theory and Its Importance in the Organization al Psychology Context . Psychology Research, 315-322 .

Krohn, M., Lizotte, A., & Hall, G. (2009). Handbook on Crime and Deviance. Springer.

Marks, I. M. (1987). Fears, phobias, and rituals: Panic, anxiety, and their disorders. . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McHugh, R. K., Hearon, B. A., & Otto, M. W. (2010). Cognitive behavioural therapy for substance use disorders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America.

NICE. (2022). Depression in adults: treatment and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

Rones, M., & Hoagwood, K. (2001). School-Based Mental Health Services: A Research Review. Clinical child and family psychology review, 223-41.

Salkovskis, P. M. (1991). The importance of behaviour in the maintenance of anxiety and panic: A cognitive account. Behavioural Psychotherapy, 6–19.

Stephens, A., Bohanna, I., & Graham, D. (2017). Expert Consensus to Examine the Cross-Cultural Utility of Substance Use and Mental Health Assessment Instruments for Use with Indigenous Clients. Evaluation Journal of Australasia, 14-22.

Vasey, M. W. (1995). Social anxiety disorders. In A. R. Eisen, C. A. Kearney, & C. E. Schaefer, Clinical handbook of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents (pp. 131-168). Jason Aronson.