Research Objectives

This theory- based research focusses on women over 40 and it sought to investigate the particular challenges that affect the experience of the women in this cohort, the support systems available to them, and how their experience as a graduate student could be improved.

Keywords

Women graduate school, re-entry female graduate school, women returnees mature female students, theory of human motivation.

Bio

Yanick Séïde, M.Ed, is the Founder and CEO of Chrysalis Women Empowerment. A Certified Master Coach, facilitator, mentor, international speaker, and member of the International Society of Female Professionals. Yanick Séïde, provides life and career coaching, guiding professional women to get clarity, discover their innate talents and strengths, to have the purposeful life and career they aspire to.

Abstract

The number of mature women returning to studies at the graduate level is growing in numbers. Before reaching the decision to pursue graduate studies they weighed in the impact returning to studies would have on the family life: financial constraint and change in lifestyle. This theory- based research focusses on women over 40 and it sought to investigate the particular challenges that affect the experience of the women in this cohort, the support systems available to them, and how their experience as a graduate student could be improved. The research followed a humanist approach and the guiding theory follows Maslow’s theory of human motivation based on a hierarchy of needs. The findings of the research indicate the challenges most mutually shared were related to multiple roles, family obligations, and finances. The study also indicated that interaction with other students and faculty were important, however these interactions were not easily developed or sustained.

Introduction

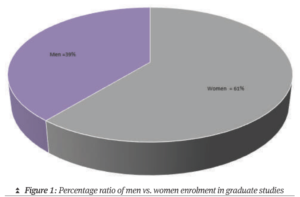

Mature female learners enroll in graduate programs in growing numbers. The focus of this paper was to consider the experiences of women over 40, who have reentered university after an extended absence; referred to as “re-entry women”. Padula (1994) defines them as “women who re-enter college or university after an absence ranging from several years to as many as 35 years” (Thomas, 2010, p.55). Bradburn, Moen, and Dempster McClain, (1995) commented that:” growing numbers of women are moving back into school following marriage and motherhood” (p.1518). Thomas (2010) notes that according to the National Centre for Education Statistics (NCES) (2009) the number of females in graduate school surpassed the number of males since 1984 (p.55). Although the number of women who have re-entered to pursue graduate studies is continuously growing, they face challenges that are a factor in their decision to enroll and impact on their lives while pursuing their studies. According to NCES 2020, women accounted for 61% of enrolment in graduate studies.

Background

The purpose of this theory-based research paper was to report the experience of older female learners who have returned to studies in graduate programs and the reasons they have returned at a later stage in life. It also sought to identify resources available to support these women and the gaps to determine what strategies and support would improve their experience. The research followed a humanist approach where according to Merriam, Caffarella & Baumgartner, (2007) learning is viewed from the perspective of the human potential for growth. The guiding theory followed Maslow’s (1943) theory of human motivation based on a hierarchy of needs “The motivation to learn is intrinsic; it emanates from the learner. For Maslow, selfactualization is the goal of learning, and educators should strive to bring this about” (Merriam, Caffarella & Baumgartner, 2007, p.282). This approach is a good match for the purpose of my research. It focusses on the experience of re-entry women, their motivation to pursue their studies, and the factors that have an impact on their experience as mature graduate students.

The following research questions guided this research:

What are the reasons women re-enter and pursue graduate studies at a later stage of their life?

- What motivates them?

What strategies and supports would improve the experience of women reentering education at the graduate level?

- What barriers do they face?

Theoretical framework

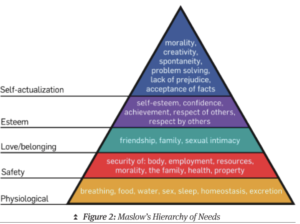

Maslow’s theory of motivation provided the theoretical basis for this study of the experience of reentry women in graduate school. This theory based on the hierarchy of needs provides the insight into the motivation of women who re-enter at the graduate level, their needs and how it affects their learning experience.

Maslow (1943) explains in his theory of the hierarchy of needs that individuals are motivated to achieve certain needs. Once a person fulfills one need, he or she will seek to fulfill the next one, and so on. The well-known pyramid displays the five motivational needs where the most basic needs are at the bottom and more complex needs at the peak (Simply psychology).

The literature indicates that the reasons re-entry women who return to studies at the graduate level are mainly for personal achievement and vocational reasons. Oplatka and Tevel (2006) state that women in mid-life seek higher education as an opportunity for personal development, self-fulfillment, and self-expression. These are linked to the motivation of self-actualization, at the peak of Maslow’s pyramid. Oplatka and Tevel also say that some women perceive higher education as a way to promote their social position. More specifically when it comes to education and qualification, which are two significant factors in a person’s esteem including self-esteem, confidence respect by others, are at the fourth level of the hierarchy. Carlson (2008) says that mid-life women pursue higher education (graduate studies) because they can make a contribution to the good of society as a whole (esteem), also contributing as an individual (self-actualization).

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs https://www.psychologytoday.com/ blog/hide-and-seek/201205/ourhierarchy-needs

Reasons why Reentry Women Pursue Graduate Studies

Current research on older adult women in graduate school provides information about women’s experience in the process of entering graduate school starting with the factors considered before making the decision to enroll. However it does not expand throughout their whole journey, nor after they have completed it.

The literature suggests that women in mid-life consider pursuing their studies for varied reasons such as self-satisfaction, intellectual stimulation to personal fulfillment and personal growth (Carlson 2008). These reasons are also suggested by participants in the research. Margaret, for example, says that she wanted to pursue her master’s primarily for her satisfaction and for professional advancement. She had contemplated it for several years. A series of factors helped her make her decision. The timing was right for her now that her children were older. Moreover, now the financial implications were no longer an obstacle because of the educational grant she received. Nancy states that she has a good job; her main reason for pursuing her master’s is for personal accomplishment. However, the literature also suggests the primary reasons are vocationally oriented, to advance their career goals, pursue a career change and seeking a new opportunity, or to gain security in their field (Perna 2004). According to Isopahkala-Bouret (2013), the majority of older students pursue graduate studies to increase their knowledge, their qualifications or both, and to apply it to their work and improve their performance in order to avoid redundancy at work. She also notes that personal development does not exclude vocationally oriented interests. Carlson (2008) also says the desire to pursue a career change and seeking new employment opportunities as particularly evident amongst working women. The idea of change as a reason for pursuing graduate school is particularly evident in responses by mid-life women in the workforce.

For working women who were employed, the desire to pursue new and different employment opportunities are characterized by responses including “new field”, “enhanced employment opportunities”, “better employment”, “more marketable”, hoped to make contacts to help me find more satisfying employment” and “a career change in midlife” (p. 43).

The same observation is also present in the empirical research Oplatka and Tavel, (2006) comment that women in midlife turn to higher education to satisfy their desires and needs, to seek self-fulfillment and growth. Padula (1994) mentions that the ability to contribute financially and experientially to the family and the need to review the roles of family and marriage as other contributing factors to the women’s decision to reenter to studies.

Oplatka and Tavel, (2006) also mention that women in midlife turn to higher education to satisfy their desires and needs, to seek self-fulfillment and growth. Women around the world reported these motivators, and despite the differences in cultures they share the same doubts American women have, for instance, including women in Israel. O’Barr, (1989) notes the following about the women in Israel:

Similar to American women who felt doubtful about prioritizing their own aspirations, accustomed as they are to putting the needs of others ahead of their own, the study participants had to reach midlife before they could liberate themselves from societal norms and family responsibilities that usually impede women’s development, particularly in family oriented societies (as cited in Oplatka& Tavel, 2006, p.72).

Although women represent a significant portion of graduate students, the decision to enroll in graduate school involves many considerations. When I contemplated returning to school and pursue a Master’s degree, I questioned if the investment was worth it at this stage of my life. I would have to dip into my savings for my retirement; I wondered if I would have enough time to replenish my savings by the time I retire. Perna (2004) says that women might evaluate the cost benefits of pursuing graduate studies. They would consider the time away from the workforce for bearing and raising children and the shorter window of opportunity to benefit from pursuing graduate studies.

I was not only considering the monetary aspect; I also weighted the time investment involved. I would not be as available to my family. Although my children were grown, there were still demands on me as a mother’s role does not stop even when the children are grown. Also at the time I decided to enroll I started a new position at our Head Office as a Corporate Learning Consultant, This change of position involved a steep learning curve. I had to shift to a new corporate culture and priorities to meet the needs of the organization at the national level. I wondered if I would have the energy to study and keep up with the assignments now that I had to travel frequently. I already was coming home quite tired from my work; I was not sure if I was up to the additional demands I was going to face. However, I saw this investment was worth it because I would have self-actualization; I would pursue something that gave me satisfaction, besides the added credential and knowledge I would bring to my practice. According to Carlson, (1999) women in mid-life who pursue studies for two reasons: because they want to provide for themselves and an altruistic reason: to ensure the welfare of others. Women in this middle stage of development have an interest in graduate studies because they see how their education can contribute to the greater good of society, leaving a legacy for future generations. One research participant, Danielle, who has two sons in their 20s, says that one of the reasons she decided to enroll in the Master’s program was because she wanted to be a role model for her sons and to encourage them in continuing their education.

Re-entry women also see the benefits that advance education offers the individual, the need for self- actualization as per Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Thomas (2010) notes that women took time before making the decision to become a graduate student but once they made it, it was a firm decision, they did not second guess themselves. Larson Carlson (1999) also notes that women in mid-life who are employed see that pursuing advance education increase the possibility of a career change, new employment and better employment opportunities in mid-life.

Motivation

Studies revealed that older women students have more motivation than their younger female counterparts. Thomas (2010) noted that older women students performed better at the graduate level than when they were at the undergraduate level. The women applied their life experience to their new career as a student and admitted to being more disciplined and prepared than when they were younger. They had to be very adept at time management to meet all the demands they had to meet in their different roles. I agree with Thomas’s statement regarding the motivation of re-entry women. As a re-entry woman myself, I find that I am more motivated than I was during my undergraduate studies. Although I was a good student, my motivation was not personal, it was a matter of getting through that stage in my life to go on to the next phase. Post- secondary studies was something that I was expected to do. Now, I am enjoying studying more than when I was younger, even though I am very busy with work and family responsibilities. I see them as something positive because they enable me to harness my full potential; it gives me a great sense of accomplishment

All of the women who participated in the interviews were interested in personal development and new career opportunities. For example, Michelle said that a few years back she wanted a change. She ceased an opportunity in a federal organization, however, during the period of budget cuts in the federal public service, and the reorganization that resulted, her position was declared surplus and she was subsequently laid-off. Fortunately, she received an education allowance as part of the severance package. Having the educational allowance facilitated her decision to enroll in a master’s program. The timing was right as her children were adolescents, and she did not have to worry about financing her studies. She had been contemplating doing her master’s for several years for herself and also professionally. She was aware that she needed it for advancement in her career. She also recognized that this was one of the deciding factors in the selection of who would be laid-off.

I have been contemplating for some time taking the master’s. I wanted to do it for myself but also wanted to advance professionally. Having a master’s when applying for a job – it matters and the fact that I did not have a master’s – it mattered for the lay-offs.

Isopahkal-Bouret (2013) noted that older students want to increase their qualifications and broaden their knowledge as a means to gain a recognized qualification that will have a positive effect on the future of their career. She also commented that some students have concerns about redundancy at work and feel that having a graduate degree can play in their favor.

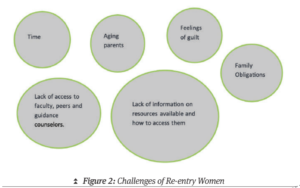

Challenges

Mid-life female graduate students face many challenges. They are at a phase in their lives where they have multiple roles; they habitually have a career, a family, a spouse, and aging parents. Role conflict is a reality they face; harmonious family life and studies are a balancing act. If they have grown children, they frequently have to look after grandchildren. Because women bear the major responsibility of caring for elderly and other dependent relatives, this can be a barrier to their participation (Heenan, 2002). As highlighted by Hillary, who cared for her mother for two years, at one point she had to withdraw because the demands of caring for her mother were too great. Later, she had to provide care for her daughter who had a medical emergency. Even for women who do not have young children family demands can be great and be a constraint in pursuing their studies. Carlson (2008) notes that women at this stage have lives filled with multiple demands on them. The additional demands of graduate studies add stress to the women’s lives. Time and again, to avoid conflict within the family they will opt to study part-time, thus prolonging the completion of the program. The impact of the added stress of graduate school on the women is connected to several factors in their lives such as the many roles they balance. Also comments that age-related changes occur in the middle years of life. Similarly, the women were cognizant that the physical and mental changes they experienced were more than the normal aging process; they recognized this being the impact of stress:

The stress of graduate school is probably a significant contributor to the health alterations that midlife women experience. Whether these changes reflect the natural progression in the aging process or are potentiated by stress that is both self and externally induced is unclear (p.44).

Müller (2008) also reports that some women experience financial or health problems. Wiest (1999) discusses why the greater domestic responsibilities women have than men make it more difficult to pursue studies later in life. There are several areas the women interviewees found frustrating or difficult. For example the lack of understanding or support from family and friends: not enough time to do everything, juggling work, family, school and time for themselves causing stress and exhaustion (Padula, 1999). Padula further discusses how their added responsibilities affected family relationships and that it sometimes put strains on the family.

Isopahkala-Bouret (2013) notes that students in their 50s may experience self-doubt about their ability due to their age; however, research has shown that older students have academic and intellectual abilities as good as younger students. Padula (1994) also notes that although re-entry women have developed many skills through experiences such as homemaking, parenting volunteering. These experiences are transferable to their continuing schooling and work, they may have problems with self-concept and self-perception, lack of confidence. According to Thomas (2010), although recent statistics show that women return to studies at the graduate level in record numbers, the literature does not address their path to return to graduate school after a span of 20 years or more. Wolf (2009) notes that learning settings, where there are opportunities for connection and for building trust and confidence in educational personnel, are important for older adult women learners. Discussion boards, group projects, collaborative projects, and dialogical classroom interactions are suggested to provide a framework conducive to bonding and support. Nancy, one of the research participants, for example, says that she did not need support but she is sure that there might be some support for mature graduate students. She did not bother looking for it. It is not clear why she was not aware if there was any support that might be available to her. Might it be because there was no support available or that the institution did not provide information at the time of enrolment, for example in an information package or as part of the orientation?

Padula and Miller (1999) note that women expressed that they were disappointed with the lack of relationships with faculty. They discuss the lack of support or clear support from faculty. Participants felt the younger female faculty were not very supportive, but they felt, the older female professors were very supportive. Peters and Daly (2013) also comment that returners lack information and mentoring to help them in the transition from a practitioner to a graduate student. They seldom have the opportunity to have direct access to professors, resources such as academic advisors and other university resources. Hillary, one of the women I interviewed recalls that after she had e-mailed the institution to get information on the program she was interested in, a representative from the institution called her. After several follow- ups she enrolled and the representative explained the different options to pay tuition but did not offer information on services or support that could be available to her if any were available. However, Thomas (2010) contradicts findings from other studies, stating that the participants report that re-entry students receive help and encouragement from graduate school faculty members.

The women I interviewed had a variety of challenges: family obligations, juggling multiple roles and the lack of time. Nancy expresses that time and money are a challenge, she also says that she manages her time in this order of priority: children come first, then her job and then her studies.” If something were to happen, the children would take priority and school would suffer”.

They see their family obligations as their biggest challenge. They express that they feel guilty for not being there for their family. Although the participants do not have young children, they believe that family obligations sometimes conflict with their academic commitments. They all express feelings of guilt; they feel that they are taking time away from the family. Margaret, for example, feels that sometimes she spends too much time on the computer.She also says that her family through all this is supportive:” I want to be there for them I realize that going back to school might not be a good thing”.

Support

The research indicates that support systems have a significant value to the success of re-entry women at the graduate level. Roberts and Plakhotnik (2009) note that informal support from peers is particularly important to adult learners. This basis of this statement is the fundamental principle that graduate students share similar worries and issues and that fellow students would relate and understand the reality of being a graduate student. According to Müeller (2008) an important aspect of the women’s learning communities is based on meaningful interaction with content, faculty, and classmates. For women in graduate school, social capital in the form of support systems such as significant relationships with family, friends and peers is crucial to the successful completion of their graduate programs.

According to Arric (2011) the support available to women from their family members, peers, school personnel and church members contributes to defining a successful path to their graduate education. She also notes that women with a higher level of income experience less stress than women with a lower level of income. Peters and Daly (2010) note that graduate students have special needs however graduate program that are used to direct pathway students do not usually accommodate those needs. They also say that returners lack information and mentoring while they make decisions about transitioning from practitioners to graduate students. They often do not have direct and continuing access to professors, academic advisors and university resources.

Maslow’s theory and women in graduate programs

Maslow (1943) states in his theory of human motivation, that people are motivated to achieve certain needs. These needs are classified in a hierarchy where once a certain need is met the individual will strive to achieve another one, and so on. The basic needs or deficiencies are physiological needs that must be met before a person is motivated to achieve the higher level growth needs. Subsequently when these needs are satisfactorily met the individual may be able to achieve the final need in the hierarchy : self-actualization. Maslow (1943) defines self-actualization as the “desire for self-fulfillment” (p.382). Merriam et al. (2007) describe the final need of an individual as the longing to achieve their full potential, what they are capable of accomplishing. They further note that Sahakian (1984) says that Maslow views the primary goal of learning as a form of self-actualization.

Research shows that before deciding to enter graduate studies, women say they took into account the financial implications that returning to school would have on their family, similarly ensuring the well-being of the family. Attending to these needs, which correlate with the second level of the hierarchy (safety) was essential before women would undertake the journey to graduate school. Subsequently the needs at the third level of the hierarchy, love/belonging are addressed. Mid-life women juggle multiple roles and they see family responsibilities as a major challenge for them. Balancing the additional demands of graduate studies and the family responsibilities while maintaining the family dynamics are important to women (Carlson, 2008; Heenan, 2002).

The studies similarly reveal that reentry women are primarily motivated to pursue graduate studies for vocational reasons (Carlson, 2004; Isopahkala-Bouret 2013; Perna, 2004). They further indicate that women expressed that they re-entered studies in pursuit of self- fulfillment and growth (Carlson 2008; Oplatka & Tavel, 2006). These two motivators for re-entering correlate respectively with the fourth and fifth level in the hierarchy: the esteem need and the self-actualization need. The two are not attended to in isolation, or consecutively, both needs in this case are addressed concurrently. The esteem need relates to the sense of high-evaluation of oneself, self-respect or self-esteem, by realizing achievement, thus showing capacity and gaining respect and esteem of others. The self-actualization need is associated with the desire to reach one’s full potential (Maslow, 1943). Returning to school provides a context where two levels of the hierarchy are fulfilled concurrently.

Conclusion

The studies show that women labour over making the decision to go back to school. After considering the financing of their studies, one of the critical factors they consider is the impact that going to school will have on their family life. The situation does not seem to have changed much in the last ten years despite the fact that women return to studies at the graduate level in growing numbers. Could this be interrelated with the fact that the division of work is unequal between men and women and that women take on the bulk of family obligations, whether they are domestic chores, child care or the caring of sick or elderly parents?

The reasons for deciding to go back to school are primarily vocationally oriented; however, women also express the need for self-satisfaction self-fulfillment and growth. Many of them had aspirations to pursue graduate studies but delayed it due to family constraints. Re-entry women report the lack of support mechanisms available to them at school or in the community. The literature indicates that interaction with faculty and fellow students was an important source of support. It also suggests there is a lack of career guidance and mentoring. There is a dichotomy in terms of the influence the family has on the experience of re-entry women: it can be a challenge, yet it is the source of great support and strength for the women. They say that they get their support mainly from their family, on the one hand; however, they also express that their major challenge is their family obligations.

The participants expressed a need for more access to financial support for re-entry women who are returning to pursue graduate studies as it has an impact on their families. They also indicated that universities should provide information on support systems that are available to them.

Recommendations

Research shows that mature reentry women in graduate school do not have as much access to faculty, peers and guidance counsellors as students who enter graduate school directly after completing an undergraduate program. It would be beneficial for these women if universities provided an orientation that would include information on the resources available to graduate students and how to access them. Also, a peer mentoring program where students who are at a later phase of their graduate program mentor new graduate students would provide support for re-entry women in the transitioning to being a graduate student.

Further research on re-entry women at the graduate level, in particular women over 40 would further increase knowledge on their particular needs. It would also help in identifying ways to broaden access to graduate school and have support systems in place to assist them during their studies.

References

Arric, L. (2011). An investigation of women’s perceived stressors and support systems while enrolled in an online graduate degree program. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from ProQuest LLC. (UMI Number: 3497347)

Bradburn, E.M., Moen, P., Dempster-McClain, D. (1995). Women’s return to school following the transition to motherhood. Social Forces, 73, 1517-1551.

Carlson, S.L., (2008). An exploration of complexity and generativity as explanations of midlife women’s graduate school experiences and reasons for pursuit of a graduate degree. Journal of Women & Aging, 11 (1), 39-51.

Heenan, D., (2002). Women, access and progression: an exploration of women’s reasons for not continuing in higher education following completion of the certificate in women’s studies. Studies in Continuing Education, 24 (1), 39-55.

Isopahkala- Bouret, U. (2013). Exploring the meaning of age for professional women who acquire master’s degrees in their late 40s and 50s. Educational Gerontology, 39: 285-297.

Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50 (4), 370-396 Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. Available: https://www.psychologytoday.com/ blog/hide=and-seek/201205/ourhierarchy-needs

Merriam, S., Caffarella, R., Baumgartner, L., (2007). Learning in adulthood (3rd Ed.) San Fr ancisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Müeller, T. (2008). Persistence of women in on-line degree completion programs. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, 3 (2), 1-19.

Oplatka, I., & Tevel, T. (2006). Liberation and revitalization: the choice and meaning of higher education among Israeli female students in midlife. Adult Education Quarterly, 57 (1), 62-84.

Padula, M.A., (1994), Reentry women: A literature review with recommendations for counseling and research, Journal of Counseling & Development, September-October 1, 73.

Padula, M.A., & Miller, D.L. (1999). Understanding graduate women’s re-entry experiences. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 23 (2), 327- 344. Perna, L. W, Understanding the decision to enroll in graduate school: Sex and Racial/Ethnic Group Differences. Journal of Higher Education. 75 (5), 487-527.

Peters, D. L., & Daly, S. R. (2013). Returning to graduate school: Expectations of success Values of the degree, and managing the costs. Journal of Engineering Education 102 (2), 244-268.

Roberts, N.A., Plakhotnik, M.S. (2009). Building social capital in the Academy: the nature and function of support systems in graduate adult education. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education 122, 43. Available: http://www. simplypsychology.org/maslow.html

Thomas, C.M. (2010). “No hesitation; I would do it again:” Women over 40 who enroll in graduate school. Journal of Ethnographic and Qualitative Research, 5 (1), 55-67. What Is Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs? – About.com Education. (n.d.). Available: http://psychology.about. com/od/theoriesofpersonality/ss/ maslows-needs-hierarchy

Wiest, L.R. (1999). Addressing the needs of graduate women. Contemporary Education, 70 (2), 30-34.

Wolf, M.A. (2009). Older women learners in transition. New Directions for Adults and Continuing Education, Summer 2009, (122), 53-62, DOI: 10.1002/ace.334. 10.1002/ace.334.